When Empathy Becomes Performance

Whiteness, Suicide, and Who We’re Allowed to Mourn

This last week has been a nightmare. Even more nightmarish than usual over the last nine months.

It began with the death of Charlie Kirk. And I hate even mentioning his name, because I’d been researching him for my Meet Your Overlords series for months. I intended on releasing the profile earlier this week, but decided to hold off after receiving threats across social media.

And honestly, the entire ordeal highlighted something much bigger: how whiteness demands that we perform empathy.

What I Mean By Whiteness

When I say “whiteness,” I’m not talking about skin color. I mean it the way critical race theorists like Cheryl Harris, Ruth Frankenberg, and bell hooks taught us:

Whiteness is the ideological framework that defines what is “normal,” “civilized,” or “valuable” in ways that privilege white people and oppress Black, Brown, Indigenous communities and people of color. It functions as the default standard against which all others are judged.

And it succeeds in doing its job. Whiteness doesn’t just normalize oppressing BIPOC communities; it ostracizes anyone who falls outside its “default standard”: LGBTQ+ people (with a special hatred towards the trans community), neurodivergent people, people with disabilities, people living with mental health and substance use, and people facing houselessness.

Whiteness defines whose suffering is “worthy” of compassion, and whose isn’t.

The Performance of Empathy

After Kirk’s death, the feeds were flooded with “thoughts and prayers.” It was surreal to watch.

This was the same man who used high school students as props for his TikTok content. The man who said he would force his 10-year-old daughter to carry a pregnancy to term. A ten year old child. The man who declared that Black women “do not have the mental capacity” to compete with men. The man who said he would “get off the plane” if the pilot were Black.

And yet, we were expected to mourn him publicly.

What was worse than the performative empathy was the condemnation of any other reaction. The people he targeted with his hate were suddenly being villainized on a national scale for not extending the very empathy he not only denied them; but had spent his career harming through rhetoric. Even people I consider close to me joined in tone-policing, as if the real harm here was not Kirk’s legacy of dehumanization but how the people he hurt dared to grieve differently.

The contrast couldn’t be clearer. When only days later, Trey Reed, a 21 year-old Black student was lynched on the campus of Delta State University. There was no national day of mourning. No flags lowered to half staff. No tidal wave of white “thoughts and prayers.” His death was not treated as a loss to the nation. And that silence is the other side of whiteness.

It’s not just about who is mourned publicly, it’s about who is denied mourning altogether. The heart of this cruelty was always anti-Blackness, the very foundation of whiteness itself. That truth can’t be softened by selective mourning. And then I remembered: This selective empathy is at its core.

I’ve Lived This Before

While whiteness robs all of us, its sharpest edge has always cut against Black people. My story sits inside that larger truth. And it shaped how I was allowed, and not allowed, to grieve even within my own white family.

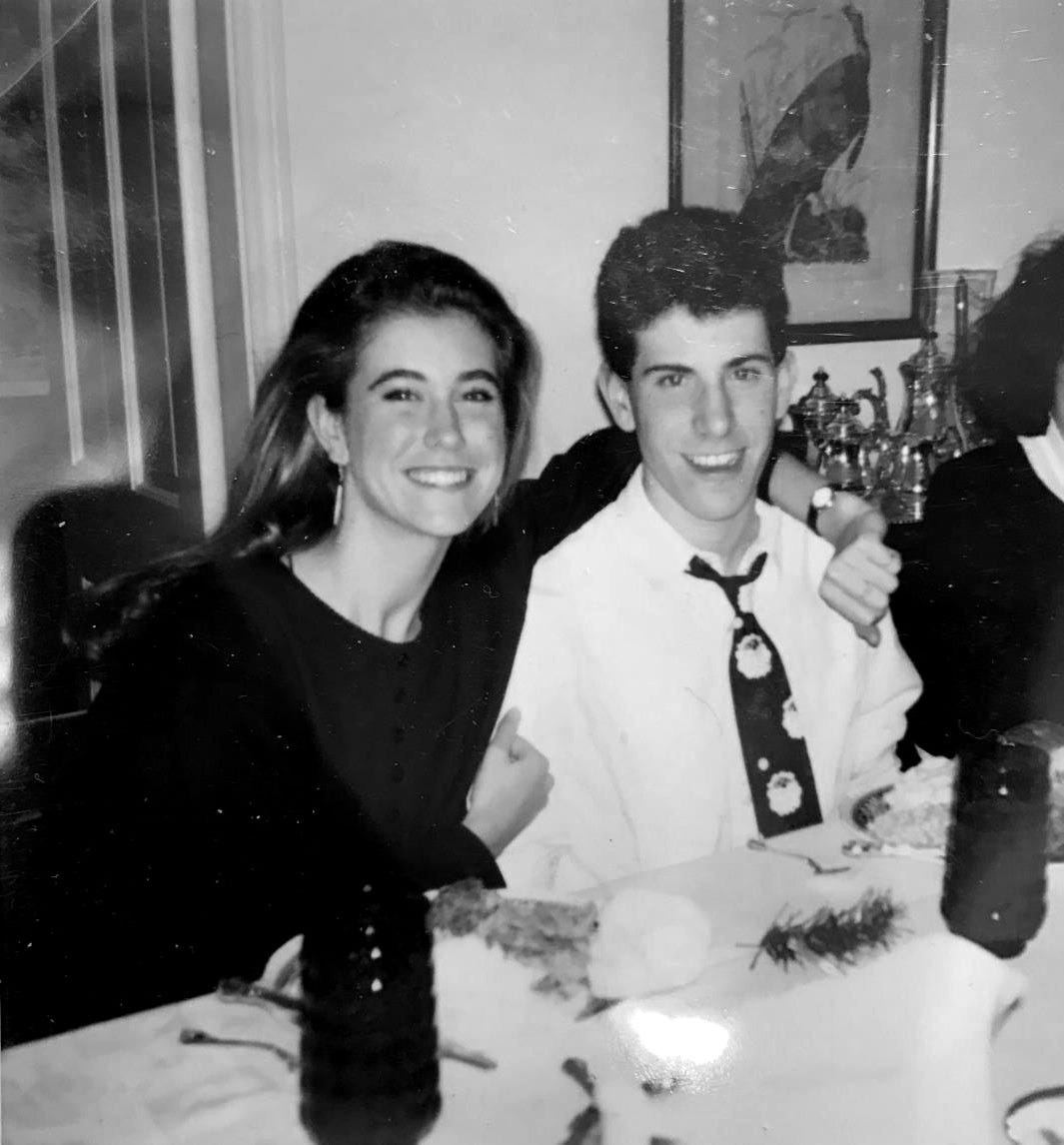

I grew up in a white, Catholic, middle-class suburb about 40 miles north of Chicago. I’m the fifth of six kids. Privileged.

When I was ten, my oldest brother Paul died by suicide. Just weeks earlier, I’d learned about the “capital sins.” Basically those sins where there is no redemption. The opposite of “get of jail free card.” You’re going straight to hell. So after our mom found Paul, my sister found me banging on the floor crying and asked, “what are you doing?” I said, “He’s in hell!” She quickly snapped, “That’s not true, stupid.”

Thank God she said that.

But the world reinforced it anyway. Kids at school told me my brother was burning in hell. One of my friend’s moms crossed the street just to scream in my face that I was trash, and so was he. Seventeen months later, my sister Casi also died by suicide.

I couldn’t mourn. Whiteness didn’t let me mourn. My siblings weren’t seen as “worthy” of mourning. Suicide meant they were less than. Their battles invisible. Their efforts unrecognized.

If Paul or Casi had died of cancer, the story would have been different. They would have been remembered for their courage. Honored for their fight. That was my deadly serious childhood wish: that they had died of something more “acceptable,” so that I could grieve them without shame.

Whiteness Stigmatizes All of Us

The construct of whiteness didn’t just deny dignity to my brother and sister. It trained me to hate them too. To bury my grief. To believe the lie that their deaths were a reflection of moral failure.

It took trauma therapy like EMDR and parts work (IFS) to start untangling the truth. I began visiting their graves every Monday. I couldn’t believe they had been buried just miles away, and I had spent most of my life avoiding them. Now, I visit because I love them. Because I know suicide is not weakness. It is a last resort when pain feels inescapable.

And I visit because I see the way we failed them. My family. Our community. Our culture. The broader society that tells young men to bury their emotions. That shames them for feeling. A culture that stigmatizes mental health so deeply that sometimes suicide feels like the only way out.

That’s where the blame belongs.

Not on Paul or Casi.

Conditioning, Trauma, and Liberation

I think this is why so many complex trauma survivors resonate with liberation movements. Complex trauma is conditioning. You adopt beliefs that aren’t yours to survive, beliefs about worth, love, belonging. That conditioning disconnects you from yourself.

So when survivors begin to deconstruct our trauma, we start to take inventory of what is truly ours and what was imposed on us. And in doing so, we start to recognize how whiteness works the same way. Because whiteness is a cultural conditioning that feeds us “acceptable” beliefs and demands performance, like empathy for some, and apathy for “others.”

What I’ve learned from grief work, especially from other cultures, is that mourning is meant to be sacred and communal. In Indigenous traditions, in African diaspora practices, and even in the growing work of death doulas, grief is allowed to be out loud. It is honored, witnessed, shared. Whiteness strips us of that. It tells us to grieve quietly, privately, or not at all. It pathologizes grief, instead of recognizing it as a human truth. My siblings deserved that kind of reverence. We all do.

The more we see how whiteness shows up in our lives, the more we can divest from it. We can stop letting it dictate who is worthy of mourning, who is worthy of empathy, who is worthy of love. When I stand at my siblings’ graves, I know they deserved better. They deserved to be remembered with the same reverence as anyone who fought an impossible battle. They deserved to be loved without condition. So do all of us.

The work of healing is the work of unlearning whiteness. It’s honoring who we actually are, what we truly care about, and who we really love. It’s a life embodied. It’s empathy embodied. It’s unlearning the performance that whiteness demands, and embracing the reality of who we are. Becoming our own soft landing, rooted in love. And honoring others as they do the same.

Your Clicks Aren’t Just Clicks

Your engagement—Your likes, comments, and shares—help this content reach the right people. Subscribing is free. Upgrade to paid to fund the rebellion.

Source Material & Further Reading

Guardian, “Charlie Kirk in his own words: ‘prowling Blacks’ and ‘the great replacement strategy’” — quotes from Charlie Kirk on Black women not having “brain processing power” and about Black pilots. The Guardian

Yahoo News, Fact Check: Real Charlie Kirk quote about Black pilot. Yahoo News Canada

The Observer, Zora Rodgers, “What Charlie Kirk got wrong about Black women” — detailing his remarks toward specific Black women. The Observer

Cheryl Harris – “Whiteness as Property” (Harvard Law Review, 1993). PDF via Harvard Law Review

Ruth Frankenberg – White Women, Race Matters: The Social Construction of Whiteness (University of Minnesota Press, 1993). Publisher page

bell hooks – Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism (1981); Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom (1994). Routledge page

Frantz Fanon – Black Skin, White Masks (1952, English trans. 1967). Publisher page

Audre Lorde – Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (1984). Publisher page

Thank you so very much for this education. We who have suicide, silence, and stoicism as an unhappy legacy in our families truly need your wisdom.

You demonstrate a grace of openness in sharing your pain with me. You speak a truth so few will understand in their narrow, blinkered life. Yet here you roar into my life with wisdom’s keeping. Bold. Unwavering. A truth seeker. A truth teller. May you grow from strength to strength. I’ll spark a flame with you. I’ll share my pain also. No fear. No shame.

For no Power in existence do my memories fear.

Pete JJ